Reflecting on Blood on the Tracks

By Alex Brumbaugh

Posted March 3, 2010

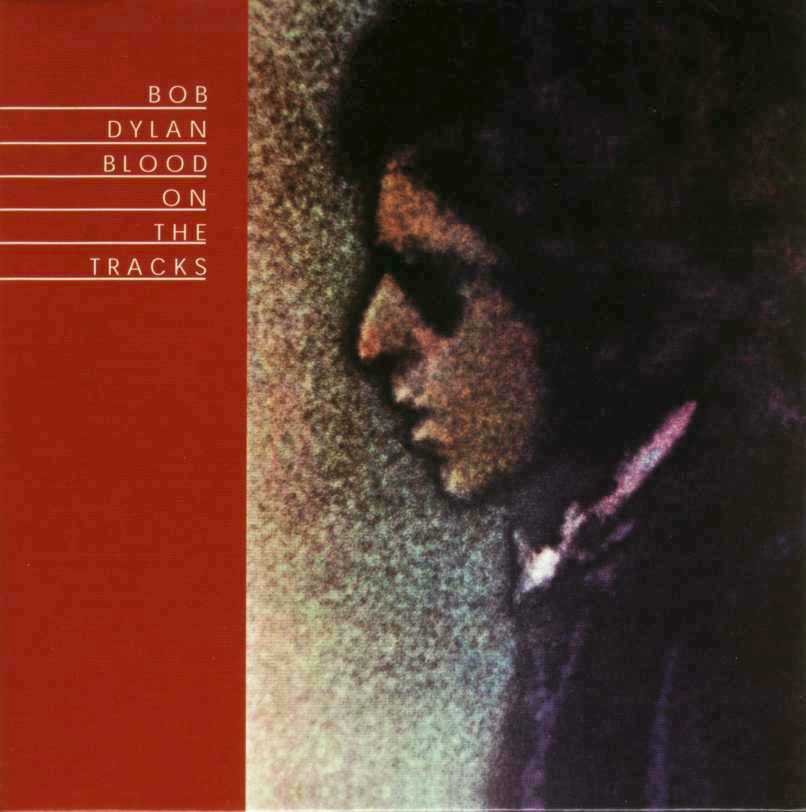

The 35th Anniversary of Bob Dylan's "best album!"

Some songs prophesize deep cultural changes, like those radical shifts

in consciousness that took place in the 50s and 60s. We imbue so much

meaning on those decades. Living through them, however, my recollection

is that “The Fifties” didn’t really start until 1956,

when Elvis released “Hound Dog.” I still remember where

I was and what I was doing the first time I heard that strident voice.

That record signaled the arrival of modern popular youth culture, accompanied,

of course, by the release in theaters of James Dean’s Rebel

Without a Cause.

“The Sixties” similarly resembled in my own experience what we think of as “The Fifties” until somewhere around 1967, when Jefferson Airplane’s “White Rabbit” announced that something very strange was happening. (But that was only an inkling – the top ten songs of 1967 included such un-portentously benign ditties as the Turtles “Happy Together ,” the Young Rascals “Groovin’,” and Nancy and Frank Sinatra’s “Somethin' Stupid.”)

Enter Bob Dylan. Whatever deep cultural transformations are ascribed to the 60’s (the Peace Movement, the Civil Rights Movement, the Feminist Movement, the Student Revolution, and – more significantly – the unhinging of the entire cultural milieu of Ozzie and Harriet) were explicitly prophesized by Dylan in 1964’s “The Times They Are a-Changin',” but the times didn’t actually change in my world view until I put the phonograph needle down on the first track of Blood on the Tracks in 1975.

This was it. We had passed the talking stages. The fat was in the fire. We were on the road.

It is hard to describe in retrospect precisely what the revolution was about that was announced by Blood on the Tracks, because the message and the medium, the instrumentation and the lyrics, and the material that Dylan selected for the album were all – in their dizzying complexity - of one piece. What exactly was happening? The only thing that you knew for sure was that someone was drilling through a wall somewhere.

The architect Frank Lloyd Wright once proclaimed that in the beginning there were two kinds of people: cave-dwellers - ancient conservatives - who chose to live in “the shadow of the wall,” and nomads - ancient liberals - who chose the relative security of mobility.

Blood on the Tracks was – if anything - about mobility. It was about traveling, and traveling light at that. It was a celebration of the road, of the spirit of the nomad. It was about leaving the shadow of the wall, and lighting out. “Let the journey begin,” was its message.

A prime influence for Dylan was Woody Guthrie. The nomads of Woody’s day – about whom he wrote and sang and whose odyssey he joined – were rootless drifters through no fault of their own, displaced by weather and bad farming practices and economic depression, and they were following a dream created by the early commercial advertising industry, a dream of oranges falling from trees and gold in the streets..

Dylan’s nomads however were in quest of another sort of dream, one that was not imposed from without but which arose from within. Their odyssey was toward spiritual, existential, and social rather than economic freedom. It was a journey of transformation, the hero’s quest.

Dylan himself has said that the songs on the album were inspired by Anton Chekov’s short stories. This Russian author is often associated with the beginning of the “stream of consciousness” literary technique. The first track on Blood - “Tangled up in Blue” - is about springing time and space, the ultimate freedom. It is an internal monologue describing the hero’s journey, an awakening to a new consciousness. “All the people I used to know are an illusion to me now.” Its writing coincides with Dylan’s cubist painting, in which convention disappears and is replaced with raw experience. Conventional moral prisms also disappear in “Idiot Wind,” the strictures of religion are lifted in “Shelter from the Storm,” and the narrative conventions of art are sprung in “Lilly, Rosemary and the Jack of hearts.” We are never quite sure where we are. That is the plight of the nomad.

But there is blood on the tracks. At the center of the journey is pain – the pain of leaving and of loss, the pain of being misunderstood, and the pain of loneliness. Life “on the road” is romantic and idyllic only from the perspective and safety of ones easy chair. The actual journey is hard. “I was standing on the side of the road, rain falling out of my shoes.” But the album’s ultimate spirit is joyous, and transcends pain, with buckets of rain and moonbeams in my hands, receiving all of the love I can stand.

Blood on the Tracks

Side one:

"Tangled

Up in Blue" – 5:42 (Sound 80 Studio - Minneapolis, MN

- 12/30/74)

"Simple Twist

of Fate" – 4:19 (A & R Studios - New York, NY - 9/19/74)

"You're

a Big Girl Now" – 4:36 (Sound 80 Studio - Minneapolis,

MN - 12/27/74)

"Idiot

Wind" – 7:48 (Sound 80 Studio - Minneapolis, MN - 12/27/74)

"You're Gonna

Make Me Lonesome When You Go" – 2:55 (A & R Studios

- New York, NY - 9/17/74)

Side two

"Meet

Me in the Morning" – 4:22 (A & R Studios - New York,

NY - 9/16/74)

"Lily, Rosemary

and the Jack of Hearts" – 8:51 (Sound 80 Studio - Minneapolis,MN

- 12/30/74)

"If You See

Her, Say Hello" – 4:49 (Sound 80 Studio - Minneapolis,

MN - 12/30/74)

"Shelter

from the Storm" – 5:02 (A & R Studios - New York,

NY - 9/17/74)

"Buckets

of Rain" – 3:22 (A & R Studios - New York, NY - 9/19/74)

Acupuncture Education Resources:

Acupuncture and Addiction Resources

Index to All Articles and Writings on this Website